Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are among the 10 most widely used drugs in the world. In 2012, there were 157 million prescriptions written for these stomach-acid inhibiting drugs.1 More than likely, either you or someone you know is taking these medications.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are among the 10 most widely used drugs in the world. In 2012, there were 157 million prescriptions written for these stomach-acid inhibiting drugs.1 More than likely, either you or someone you know is taking these medications.

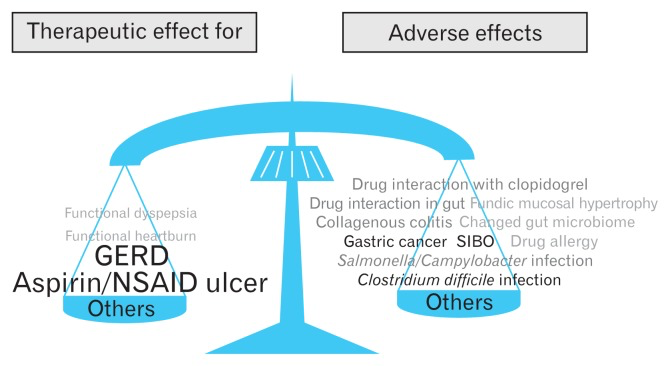

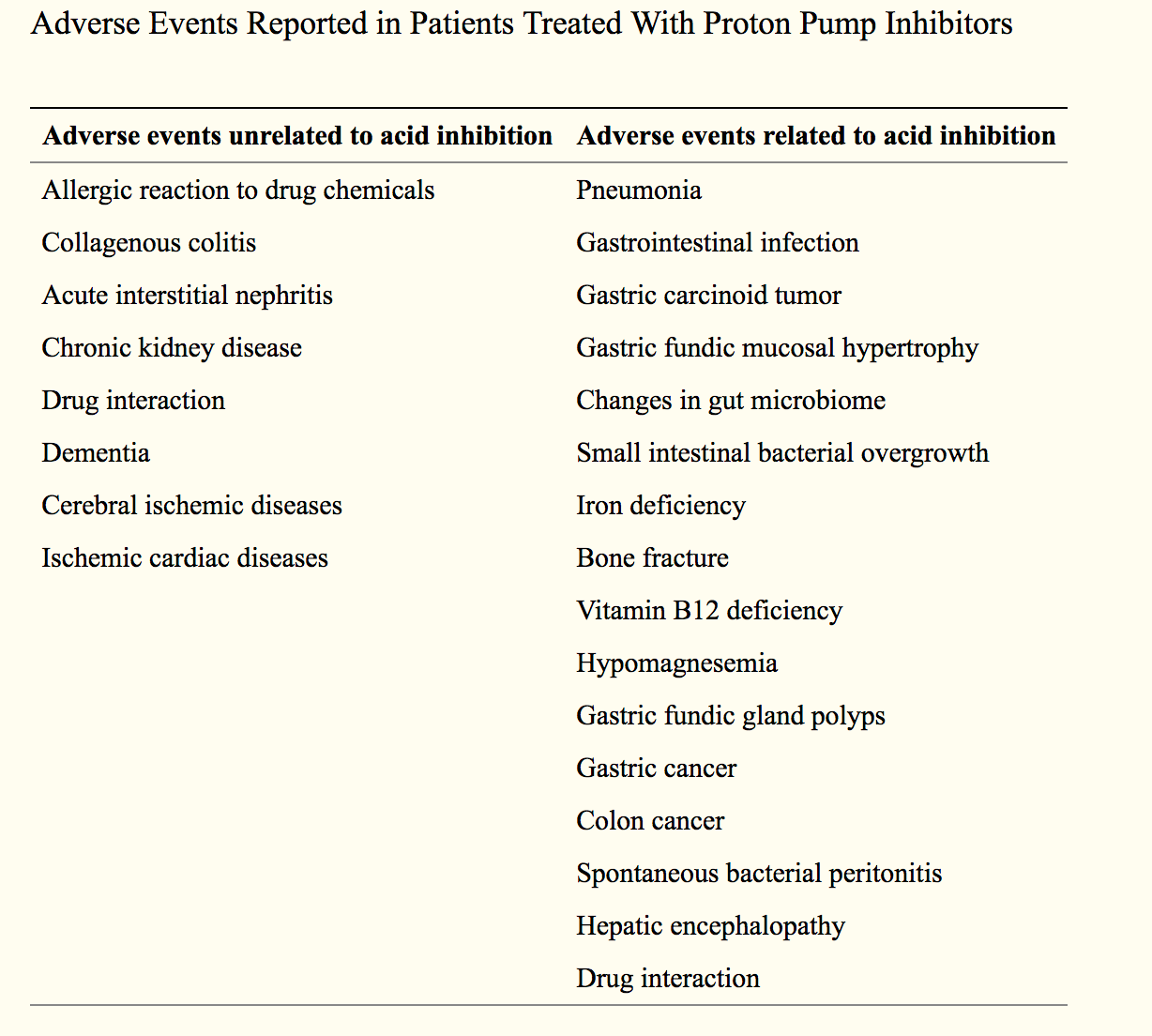

While PPIs may alleviate the problem of excess stomach acid, many people don’t realize that these drugs are associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer, pneumonia, c. difficile infections, osteoporosis (you need stomach acid to absorb nutrients such as magnesium and calcium into bones), and vitamin B12 deficiency, among other serious diseases.2

The Rationale Behind PPIs

The stomach secretes digestive fluids with a pH2 value, which creates a highly acidic environment. These acidic gastric secretions sterilize bacteria in foods that are eaten, and are essential for the digestion and absorption of various nutrients, including protein, iron, calcium, and vitamin B12.

Obviously, stomach acid that can digest food can also damage delicate intestinal mucosa. The body has protective mechanisms—including mucosal mucous/bicarbonate secretion and sphincter contraction of the gastroesophageal junction—to prevent gastroesophageal damage. But if the sphincter is weakened, stomach acid can flow back into the esophagus. The backwash of acid irritates the esophageal lining, causing heartburn and the regurgitation of food. If the condition persists, it may cause chest pain, difficulty swallowing, chronic cough, hoarseness, and disrupted sleep. Left untreated, GERD can lead to esophageal ulcers, narrowing of the esophagus, and precancerous changes known as Barrett’s esophagus.

Conventional treatments include over-the-counter antacids to neutralize stomach acid. More potent medications to reduce acid production (known as H-2-receptor blockers) decrease stomach acid production for up to 12 hours. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the “big guns” developed to block the production of stomach acid. They’re now commonly used as a first-line treatment for gastrointestinal acid-related diseases.3

PPIs work by blocking the brain’s signal to the stomach to secrete more hydrochloric acid. Sounds like a simple fix, right? But there are problems with this approach. First, is that PPIs must be taken daily to keep acid levels low. The second problem is that PPIs block the communication-response system to the brain, disrupting the entire digestive process. The continued use of proton pump inhibitors impairs digestion since the body has no way to adjust for the correct amount of acid to be released during or between meals.4

The Misuse of PPIs

A recent New England Journal of Medicine review of prophylaxis for upper gastrointestinal bleeding among hospitalized patients showed that not only is acid suppression commonly used without indication in the intensive care unit (ICU) and medical wards, but that these medications are frequently continued after discharge. For example, studies have shown that more than 60% of patients transferred from the ICU to the wards were continued on prophylactic acid suppression without indication.

The article also addresses some of the potential adverse effects of unnecessary acid suppression, including chronic kidney disease, osteoporosis, and infections. The researchers noted that for low-risk hospitalized patients, the use of acid suppression without a clear indication could be harmful.5

I’m sure it comes as no surprise that the overuse of acid-suppressing medications is

not limited to the inpatient setting. A series of studies have demonstrated that roughly 50% of outpatients on chronic proton pump inhibitors do not have indications for these medications.6 That is an enormous number of people taking medications that are unnecessary and potentially harmful.

Suppressing stomach acid secretion for long periods can have serious unintended consequences. Pepsin, an enzyme essential to the preliminary digestion of protein, needs an acidic environment to be effective. The strongly acidic hydrochloric acid pumped out by cells in the lining of the stomach also plays a direct role in the initial digestion of some foods. And stomach acidity is a built-in barrier to infection.

PPIs are one of the most difficult classes of drugs to wean people from, and therefore are highly addictive. You might wonder how a drug for suppressing stomach acid can be addictive. Imagine the PPI acting like a dam for a river. When the dam is created, a lake forms behind it. When the dam is removed, the water from the lake floods downstream. In a similar way, stopping the use of PPIs causes the suppressed stomach acid to flood the digestive system, and symptoms return with a vengeance. The result? Most people return to using PPIs, and the cycle continues.

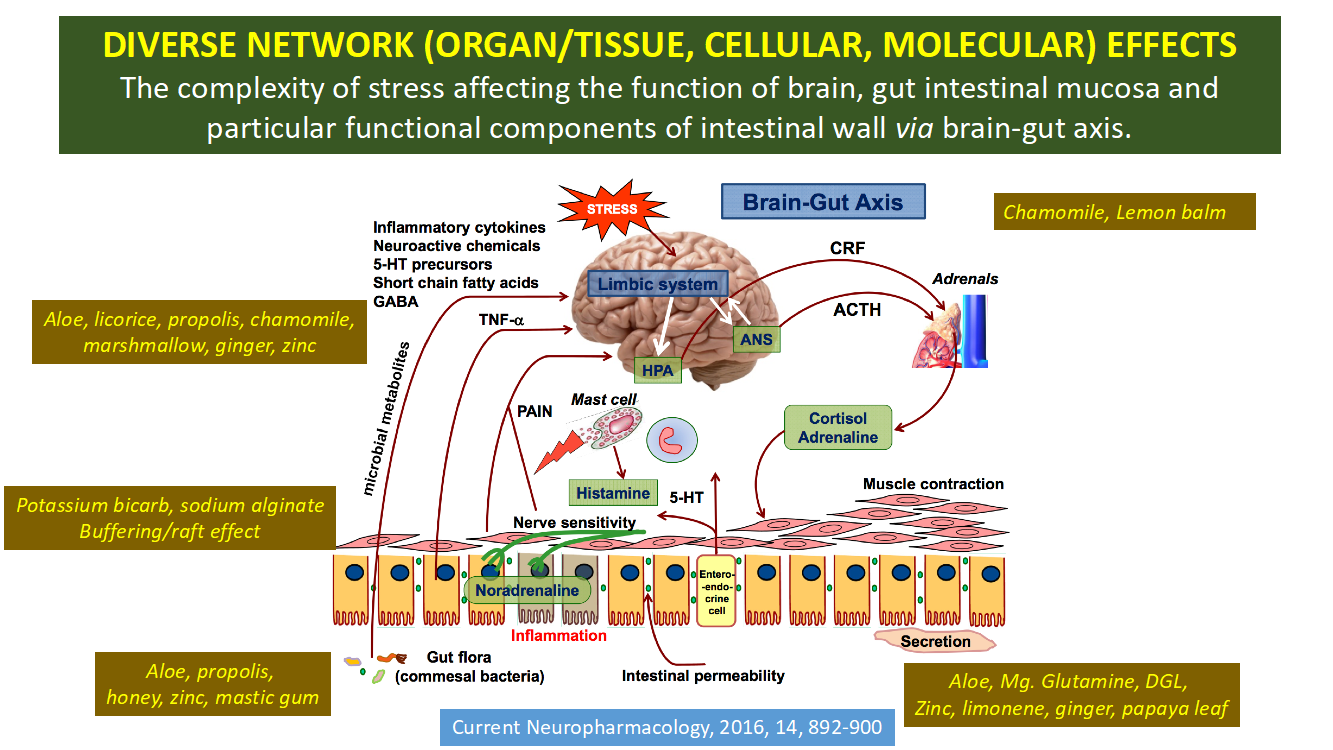

The Brain-Nervous System and Gut Connection

Although it’s not often acknowledged in conventional modern medicine, there is a direct connection between the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and the central nervous system (CNS). Researchers have found evidence that irritation in the gastrointestinal system sends signals to the CNS that trigger mood changes. Our gut and brain ‘talk’ to each other, so therapies (including herbal medicine) that support one may help the other. Interestingly, the gut microbiota continues to evolve along with human development and is influenced by various stress factors.8

Some evidence has shown that stress in the first few years of life can change the microbiota, and this change is a risk factor for stressrelated disorders in adulthood. 9,10

The Vagus Nerve and the Digestive System

Beginning in the brain, the vagus nerve travels alongside the esophagus to the stomach and other gastrointestinal organs, and is primarily responsible for autonomic regulation involved in heart, lung and gastrointestinal function. The vagus nerve controls much of the activity of the stomach, intestine and pancreas and plays a role in food processing, including:

- expansion of the stomach as food enters; contractions of the stomach to break food into smaller particles;

- release of gastric acid required for food processing;

- emptying of the stomach contents into the small intestine;

- secretion of digestive pancreatic enzymes that enable absorption of calories; and

- controlling sensations of hunger, satisfaction and fullness

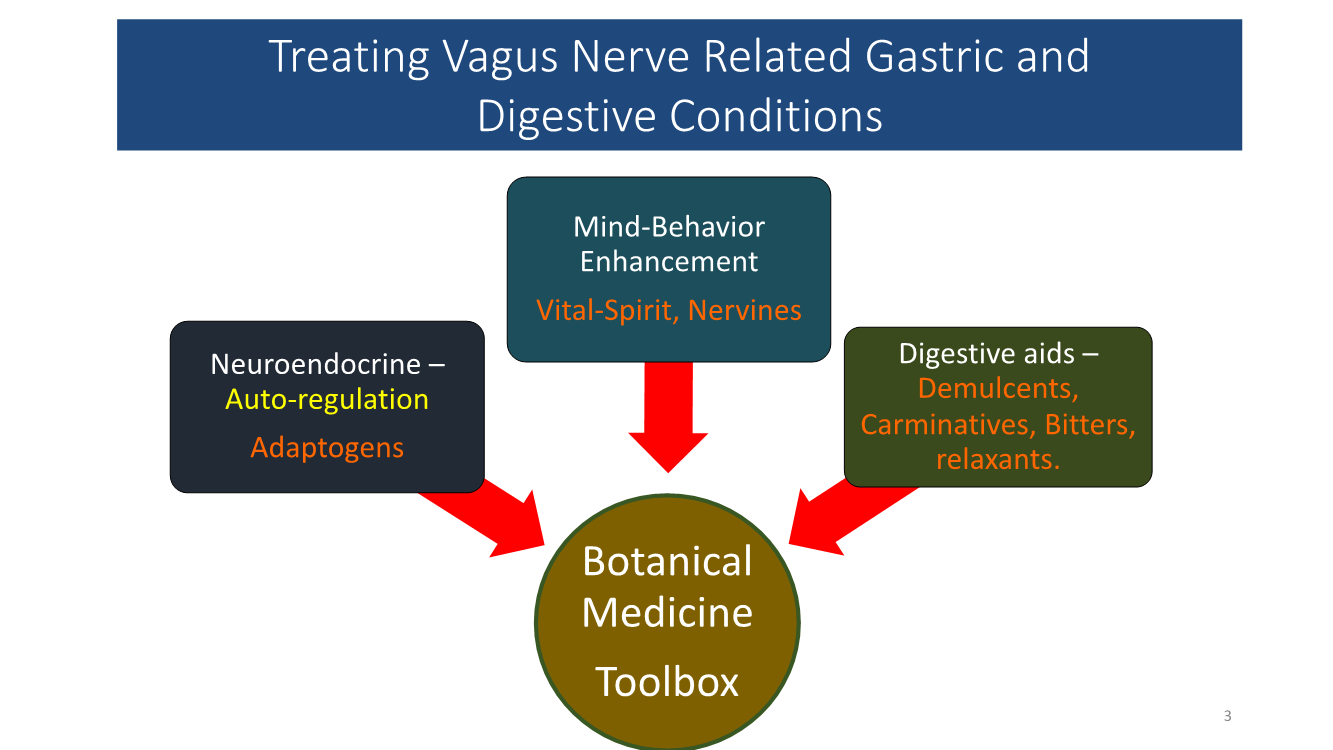

In my clinical practice, I find that the best approach for treating GERD and other digestive system issues related to excess stomach acid is to gently regulate stomach acids, while simultaneously modulating and strengthening the nervous system. Herbs, with their pleotrophic effects, are an excellent choice for supporting both the nervous system and the digestive system.

A Wholistic Alternative to PPIs

Through extensive research and clinical observation, I’ve developed a treatment protocol for GERD and other digestive tract disorders that help to restore the body’s natural self-regulatory abilities.

My protocol includes botanicals and nutrients chosen for their ability to:

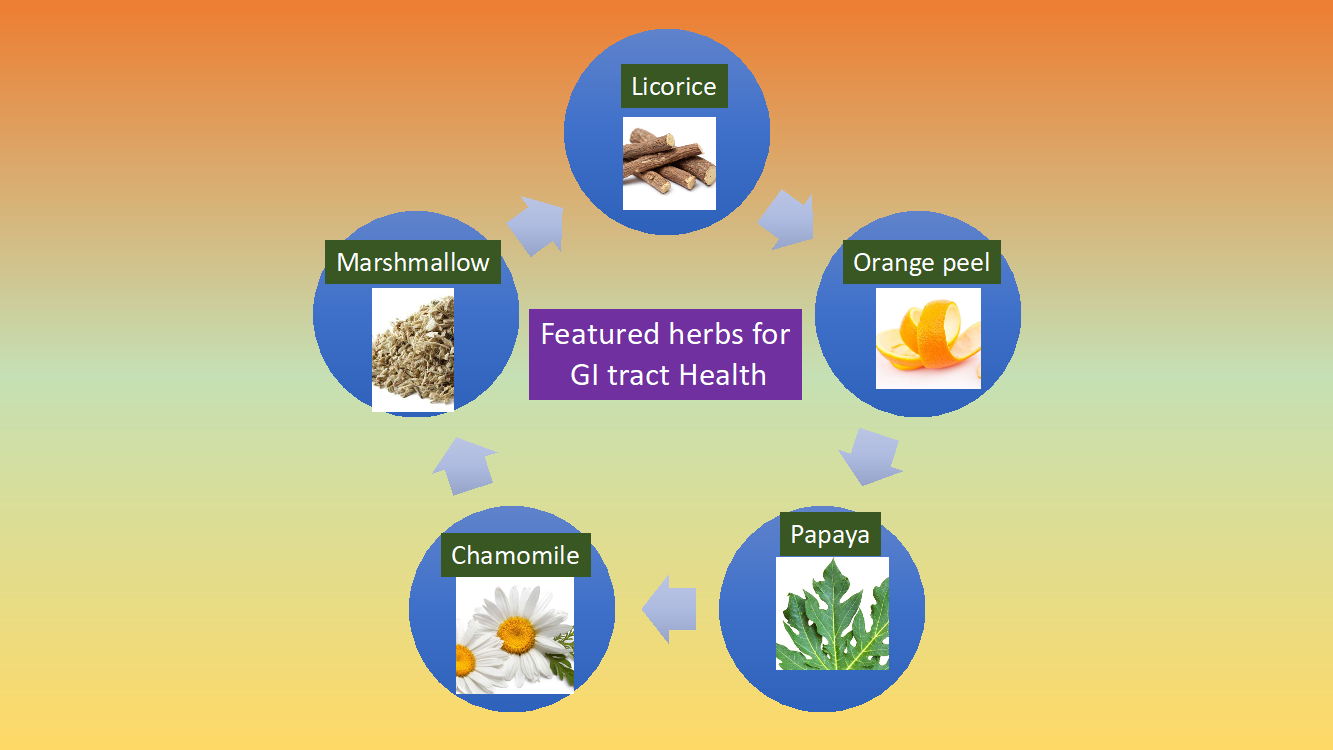

- Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) Deglycyrrhizinated root extract (DGL)

- Marshmallow root (Althaea officinalis)

- Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensisMiller) extract BioAloe 20% Acemanan

- Chamomile (Matricaria recutitaor Chamomilla recutita) extract >1% apigenin

- Mastic gum extract

- Ginger (Zingiber officinalis) extract

- D-Limonene Extract (Orange peel oil)

- Propolis powder

- Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis)

- Papaya leaf powder

- Manuka honey powder

Of these, chamomile and lemon balm offer the additional benefit of supporting the nervous system, and address the important connection between the digestive tract and the nervous system.

Other nutrients that I’ve found beneficial for digestive health include glutamine-magnesium-glycine chelate, zinc carnosine, potassium bicarbonate, and sodium alginate. Formulas that include an array of botanicals and targeted nutrients provide a comprehensive, balanced approach to GERD and other gastrointestinal disorders.

Licorice and GERD

Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) may be the best-known botanical for addressing GERD. Licorice has been used medicinally for thousands of years in both Eastern and Western medicine to treat a variety of ailments, including GI problems.

Preliminary studies suggest that a specific herbal formula containing licorice, called Iberogast or STW 5, helps to relieve symptoms of GERD and indigestion.11 Licorice also shows promise for relieving the stomach irritation caused by aspirin. An animal study found that aspirin coated with licorice reduced the number of ulcers in rats by 50%.12

I’ve long used licorice in my practice, and prefer deglycyrrhizinated licorice root (DGL) extract, which has been processed to remove the steroid-like compound glycyrrhizin. This prevents the potential problems of edema and hypertension that susceptible individuals may experience when taking large amounts of licorice.

DGL both relieves symptoms and promotes healing of ulcers, GI inflammation, heartburn and mouth sores. I’ve been recommending DGL for thirty-plus years for gastrointestinal issues including heartburn/indigestion, ulcers, and in mouth rinse solutions. My patients who suffer from heartburn, peptic ulcer disease, or gastritis have found great relief from using DGL.

Research studies support my clinical observations. In clinical studies, DGL has been found to be as effective as Cimetidine for peptic ulcers. For example, research published in the British Medical Journal comparing Cimetidine and DGL for peptic ulcer disease evaluated 82 patients who were given two tablets of DGL twice daily compared to a regular dosage of the over-the-counter medication for peptic ulcer disease. After two years on this regimen, the recurrence rate for gastric ulcers for the two groups was similar.13

In evaluating the usage of PPIs in both hospital and outpatient settings, it is obvious that these drugs are increasingly being prescribed as a first-line treatment for GERD and other gastrointestinal issues related to excess stomach acid. As I mentioned previously, the long-term suppression of stomach acid secretion has significant negative health consequences. A much better approach is to use botanicals and nutrients that regulate stomach acid naturally and concurrently, support healthy gastrointestinal function.

References

- Lam JR, Schneider JL, Zhao W, Corley DA. Proton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and vitamin B12 deficiency. JAMA. 2013;310:2435-2442.

- Weintraub, Karen, Do PPIs have long-term side effects? (March 18, 2016), Harvard Health Publications. Studies Link Some Stomach Drugs to Possible Alzheimer’s Disease and Kidney Problems – Scientific American, February 1, 2017;

- Yoshikazu Kinoshita,*Norihisa Ishimura, and Shunji Ishihara, Advantages and Disadvantages of Long-term Proton Pump Inhibitor Use, J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018 Apr; 24(2): 182–196.Published online 2018 Apr 1. doi: 10.5056/jnm18001

- Weintraub, Karen, Do PPIs have long-term side effects? (March 18, 2016), Harvard Health Publications. Studies Link Some Stomach Drugs to Possible Alzheimer’s Disease and Kidney Problems – Scientific American, February 1, 2017.

- Cook, Deborah M.D., Guyatt, Gordon M.D. Prophylaxis against Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Hospitalized Patients, June 28, 2018 N Engl J Med 2018; 378:2506-2516, DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1605507

- Michael Hochman, MPH, MD, and Pieter Cohen MD. Slow Medicine: Discontinuing PPIs, August 08, 2018, Medpage Today

- Yoshikazu Kinoshita,*Norihisa Ishimura, and Shunji Ishihara, Advantages and Disadvantages of Long-term Proton Pump Inhibitor Use, J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018 Apr; 24(2): 182–196. Published online 2018 Apr 1. doi: 10.5056/jnm18001

- HongXing Wang, YuPing Wang, Gut Microbiotabrain Axis, Chin Med J (Engl). 2016 Oct 5; 129(19): 2373–2380.

- O’Mahony SM, Marchesi JR, Scully P, Codling C, Ceolho AM, Quigley EM, et al. Early life stress alters behavior, immunity, and microbiota in rats: Implications for irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric illnesses. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:263–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.026.

- Sudo N. Stress and gut microbiota: Does postnatal microbial colonization program the hypothalamic pituitaryadrenal system for stress response? Int Congr Ser. 2006;1287:350–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ics.2005.12.019.

- Melzer J, Rosch W, Reichling J, et al. Meta-analysis: phytotherapy of functional dyspepsia with the herbal drug preparation STW 5 (Iberogast). Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1279-87.

- Dehpour AR, Zolfaghari ME, Samadian T, Vahedi Y. The protective effect of liquorice components and their derivatives against gastric ulcer induced by aspirin in rats, J Pharm Pharmacol. 1994 Feb;46(2):148-9.

- Russell RI, Morgan RJ, Nelson LM. Studies on the protective effect of deglycyrrhinised liquorice against aspirin (ASA) and ASA plus bile acid-induced gastric mucosal damage, and ASA absorption in rats, Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1984;92:97-100.

Excellent article. Both I and my wife had GERD many years ago and my wife was also diagnosed with Barret’s. We both recovered using DGL. Her gastroenterologist dismissed her recovery based on DGL use. I have recommended DGL to many folks over the years but not one was willing to give it a try.